Where Cinema, Fashion & Art Come Together

Be the first to get our news by signing up here.

Fashion in Film Festival looks at cinema through the lens of fashion, and the other way round. Each of our curated festival seasons is a labour of love that explores a new aspect of this intersection. We probe into images, stories, ideas, materials, makers and institutions. We research, we ask questions, we debate. We spark conversations. We collaborate. Above all, we champion the art of cinema – its power to move fashion and its power to move us.

exhibitions & projects

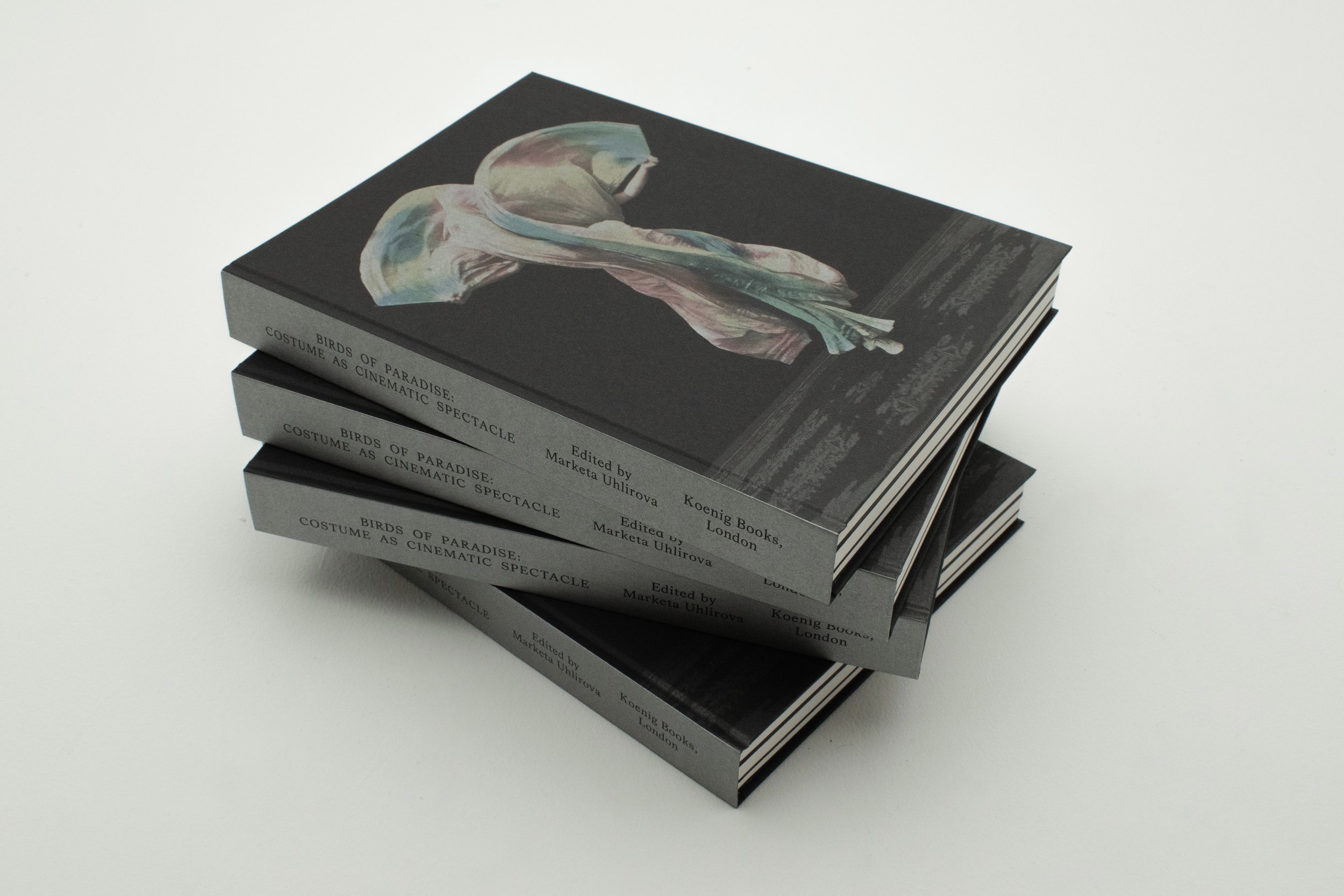

publications

essays & interviews

research

film festivals

WHAT WE DOWHAT WE DOfilm festivals

publications

exhibitions & projects

essays & interviews

research

OUR FILM The Inferno Unseen

a live performance with a musical score

by Rollo Smallcombe

WE WORK WITH ARCHIVES, DISTRIBUTORS AND SCHOLARS TO REDISCOVER RARELY SCREENED GEMS. WE ARE PASSIONATE ABOUT PRESENTING BOTH KNOWN AND FORGOTTEN CINEMA TO AUDIENCES IN NOVEL AND UNEXPECTED CONTEXTS.

‘A terrific manifesto.’

— Cindy Sherman

— Cindy Sherman

‘I was pretty blown away.’

— Jarvis Cocker

— Jarvis Cocker

‘GORGEOUS. What a triumph and achievement.’

— Stuart Comer

— Stuart Comer