New York-based artist Michelle Handelman, whose film Irma Vep, The Last Breath is included in our current season WEARING TIME: PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE, DREAM, talks to Aya Noel about women in cinema, identity and costume as a state of mind.

Aya Noel: Your last projects have been based on historic literature (Dorian a Cinematic Perfume based on Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray and This Delicate Monster on Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal). Why did you choose Louis Feuillade’s film Les Vampires as inspiration for your latest project, which you called Irma Vep, The Last Breath?

Michelle Handelmann: Recently I’ve been revisiting iconic historical texts that have impacted on contemporary culture in both visible and invisible ways. It’s the invisibility that interests me, the unsaid. In particular, the hidden queerness of both the characters and the authors. I also work from a very personal place and have been looking deeply at those things that have inspired my own vision aesthetically, philosophically, politically. When we’re young we grab onto things without really knowing why — fashion, music, films – we try them on and this layering of culture, like a layering of clothes, starts to form our identity.

I chose Les Vampires because it was high on the list of ‘things that made me who I am’. From the time I first saw the film as a teenager an image of Irma Vep has always been hanging somewhere on my wall. But why does one image imprint itself on my psyche and another doesn’t? This I need to find out, both to understand my own position in society and society’s complex doing and undoing of identity. I’ve been thinking a lot about the fundamental relationship between evolving media that’s always in flux and philosophical questions of existence that don’t seem to change much at all. How do these ideas translate across history and across media? Do cinematic tropes develop from real life or are our identities constructed through cinema and media?

AN: What attracted you to Musidora’s character Irma Vep, the prototype of the Catwoman?

MH: As a kid, long before I saw Les Vampires, I was obsessed with the American TV show Batman, and this became my initiation into the world of latex and rubber. I remember watching the show and just lusting after Catwoman’s outfits. I wanted to touch them, to bite them, consume them, I wanted to be Catwoman. I was attracted to the darkness, the forbidden sexuality and the female agency, especially in service of desire. Pleasure, power, the reveal, the conceal, the no-holds barred invisibility cloak… everything about female power was contained in that image for me.

AN: How does this relate to the portrayal of women in cinema today?

MH: In many ways the position of women in the film industry, and the portrayal of female characters has regressed since the early days of cinema. Early film actresses were often the primary headliners and box office draw. Women had fully developed roles with their own storylines. They had lucrative contracts. Now female characters are there only to serve a story played out by the male leads.

I would say that the vamp, or femme fatale character has shifted too. In the early days of cinema you had characters like Irma Vep and Theda Bara’s ‘vamp’ in A Fool There Was, who were single women, intelligent and powerful, who used their brains to get what they want. There were layers to unpack with these characters. After the war this image of women threatened the patriarchy, which was already suffering a loss of manhood due to losing so many men on the front lines, and so this type of ‘dangerous woman’ character was reduced to a caricature, a sexpot who uses her body to get what she wants, and is usually lacking in the brains department. On the whole, Hollywood still refuses to film stories that do not present a female lead as needing heterosexual love and marriage to give her life meaning.

Just look at the posters and notice whose name comes first, or who is listed in the credits. Often you see movie posters that have an image of a man and a woman, but when you look at the credits only the male actor’s name is mentioned. Clearly the woman is inconsequential in the eyes of the studios. She remains an object of desire. And we all know about the pay inequality between female and male actors, as well as the lack of female directors. We move forward very slowly because we’re so busy sliding backwards.

AN: When and why did you decide to cast Zackary Drucker as Irma? And Jack Doroshow (AKA Flawless Sabrina) as Musidora?

MH: Actually it was Jack (Flawless Sabrina) who brought me to Zackary. I had worked with Jack on my previous project Dorian, A Cinematic Perfume, which I found transformative. My work is invested with surfaces, and Jack had the entire world written on her body. Every experience was there as a witness to her life. And her onscreen power was palpable. All she has to do is stare at the camera and it’s as if the entire history of queerness is played out before you on screen. I knew I wanted to work with her again, so as I began developing Irma Vep, the Last Breath I asked her to play Musidora. As we were talking about the project it was her idea to include Zackary.

Zackary was living in LA at that time, and as I was mulling this idea over in my head I happened to be at an intimate art performance and became transfixed by this woman in the audience. I went up and introduced myself and it turned out to be Zackary! There’s many reasons why I cast both of them… Zackary, like Jack, also had this power to transform a room merely by her presence, and I was also interested in the close personal relationship between Jack and Zackary, and this transgenerational relationship of queerness became the underpinning of my whole project. I’m not interested in working with actors playing a role, but in real people who are playing a heightened version of themselves – both in their own lives and in my films.

AN: In a previous interview you said that ‘both of the actors bring to the character their own experience of living in the margins’. Could you expand on this?

MH: Yes, it’s the ability to hide in plain sight. As I began searching for meaning for the core of the project I realised it connected to my own background of being raised in a split family – one within the law, one outside the law – and the many masquerades I had to engage in to keep the ‘straight’ side of the family in the dark… to pass as a normal suburban teenager when I fact I was selling drugs and working at a massage parlour. That being ‘in’ or ‘out’ of character is something we perform everyday. And that ‘passing’ is a form of performance.

Zackary is a trans woman and so, for many years before her transition, she lived undercover as a woman in a male body. There’s always this fear around passing, as being ‘outed’ – it is something that puts you in a vulnerable position. There is nothing showy about Zackary, in fact the night I first met her she looked like a very demure woman in a twin-set and pearls, but she has this fierce intelligence that is pointed and kinetic – a crazy depth beneath the surface.

And Jack grew up a Jewish, gay man in a rough neighbourhood in 1940s Philadelphia where living undercover was necessary to survival. They have both found ways to survive in a society that tells them they have no right to exist. Musidora too has been told she has no right to exist. As one of the pioneering female filmmakers, her films have been left to oblivion, the legacy of all her achievements is wrapped up in a single character she portrayed at the age of 25. Everything after that society has deemed forgettable, erasure. Just as queer peoples’ histories remain unaccredited and invalidated, women too are second-class citizens and Jack represented all of that for me.

AN: Your film talks about themes of criminality and living undercover. This relates both to Zackary’s story of coming out, and to your past in the criminal scene. Could you explain how these personal stories of past and present come together and what broader message they communicate?

MH: All of our personal stories are embedded in the characters; particularly in the sessions Irma Vep has with her therapist. These provide the entire dialog of the film. When Zackary and I spoke about the character I told Zackary to speak from her own perspective, as if she was talking to her own therapist. I had just started therapy at the time and made a list of my issues, along with issues I imagined Irma Vep might have if she was a real person, then gave that list to Zackary to incorporate into her own struggles. I think the broader message is something that is quite universal – we all feel loss, we all want love, we all struggle with finding meaning in our lives, we all have good days and bad days, and we all have regrets. It’s these sacrifices that we make – what we give up to have one thing over another that I’m interested in. In fact, I’m exploring that further with my new project Hustlers and Empires.

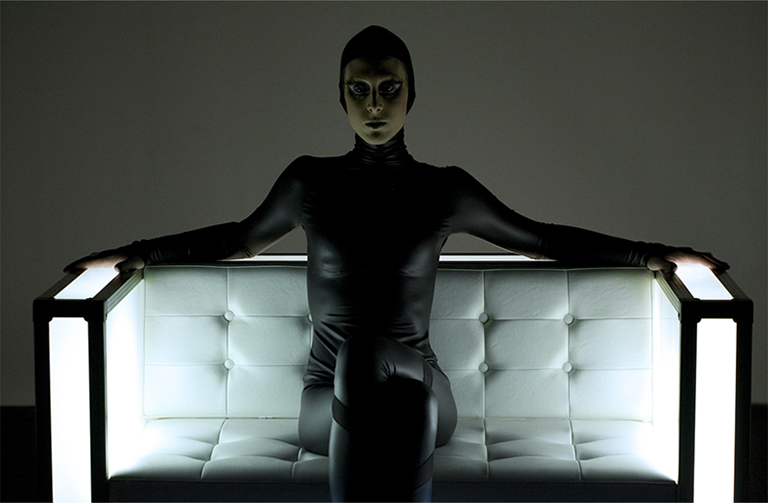

AN: Both Zackary and Flawless Sabrina’s costumes reference Musidora’s original catsuit. What part of Irma’s original costume did you want to preserve, and what did you add?

MH: I wasn’t trying to re-create the original film, and I wasn’t interested in making a period piece – so in many ways I wasn’t trying to preserve anything. I very deliberately wanted to create a completely contemporary world that had a spirit from the original film but was completely now. I worked with couture corset designer Garo Sparo on the catsuits. We kept the hood, but I also wanted the option to remove the hood, so we had several pieces to the costumes including the catsuit, corset, hood and wings. The wings are actually a nod to this scene in the original film where a ballerina is portraying the famous criminal Irma Vep on stage. The dancer has these voluminous bat wings so we made an adaptation of that. The wings are a nod to the fact that many people (who know about the film but haven’t actually watched it) think Irma Vep is a vampire because of the title Les Vampires. She is actually part of an underground gang, a so-called ‘apache’. Les Vampires is many ways is one of the first noir films. It’s essentially a cops and robbers caper.

AN: How can costumes be a part of your message (in this film, and/or in your work in general)?

MH: Masks are revealing. Clothing carries our identity, a character’s identity. We put clothes on like a second skin that covers us, protects us, creates an armour as we present ourselves to the world. In my experience, the more artifice a person covers themselves with, the deeper the pain. And within a filmic structure costumes are another surface that carry meaning.

One of my favourite cinematic moments is in Kenneth Anger’s masterpiece Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome where this disembodied, floating head removes a mask only to reveal another mask underneath, and another underneath that, and so on and so on. The psychological masks we all wear are so deeply layered that it’s difficult for one to know where one’s own identity begins. So, the ‘costume’ is really the physical manifestation of the psychological and emotional content. Yes, it may be a signifier of a position, a station in life, but in my work costumes are predominantly used symbolically and as an extension of states of being such as passion, terror, release.

AN: Your film shows primarily two spaces: the therapist’s room (a space where one revisits the past) and the ticket booth which resembles a coffin – ‘a time capsule for what might have been’. Could you expand on the way Irma Vep, The Last Breath plays with past, present and dream, and how these times correlate or oppose?

MH: The past, present and dream all co-exist simultaneously for me. In this project I was thinking about how as an artist one makes ‘works’, whether they are films, sculptures, performances, etc. that go on to have a life of their own, and how the ‘works’ themselves don’t really age, while the artist does. And the life of a work of art, that continuum, is outside of the artist’s control, outside the ravages of physical time. It’s a life dictated by the writers of history, those who decide what works of art should be given further life through reviews, reproduction, restoration, academia… If you are lucky as an artist, you produce one or two, or perhaps many works that have left their mark on society, works that have achieved immortality. The work is like a vampire in a way, feeding off the maker who gets old and shrivels up and dies. I’m of course being metaphorical here, but this power dynamic between the maker and her creation is what intrigues me. The tension between the inside and the outside.

I would say that the two main spaces in Irma Vep, The Last Breath are not easily divided into past and present; they are more about interiority and exteriority. I imagined the scenes of Irma speaking with her therapist to be ‘of the present’, yet it is also the place where the interior psyche is made exterior. Sure, you can say Irma is revisiting the past in these scenes, but remember, none of these things happened to her because she’s fictional. She’s imaginary. But Musidora is a real human being who lived a full artistic life, and all that remains is her portrayal of Irma Vep. Her ‘time capsule’ (we kept calling it ‘spaceship’ on set) is symbolic of capturing time, and that is one of the primary properties of filmmaking. Also, the interior of the capsule is a mess, thick and red, like the inside of a body, with detritus of her former glory days. It begs the question: Is that all there is? Is this what a successful artist gets as reward, a couple of cool posters and head shots, her life frozen at the age of 25?

And the moment when Irma Vep’s character moves out of her space and into the space of Musidora, the old woman in the ticket booth, is a place of transfer between what we perceive as external or internal; between life and death, between the real and the fabricated, a crossing of borders. And at that moment the creation, the ‘art work’ has consciousness – Irma Vep, the fictional character created by a real actress Musidora sees her maker. The idea of a work of art actually having consciousness – that’s the dream.

AN: Are these opposing times tangible in the costumes?

MH: I think so. threeASFOUR’s designs are so of the future. They are what Irma Vep would be wearing in 2020. And they are what Irma Vep wears when she crosses over. The catsuit, which has its own history, gets more distressed as we move through the three individual therapy sessions. The sessions start out with Irma Vep quiet and despondent, then eventually end with her embittered, almost a proud acceptance of her cynical self. Musidora, the old woman in the ticket booth, wears a catsuit that is layered and shredded as if she’s been living in it for a hundred years, but underneath there is this hint of sensuality; a black and pink satin bra and underwear, timeless in their elegance, revealing an aging woman’s desire to still feel her sexuality against her skin.

AN: Musidora was once a famous actress and movie director, she then disappeared from fame. How would you like the audience today to rediscover/remember her?

MH: I would like them to know that she existed. That she accomplished so much at a time when women didn’t even have the right to vote in this country. So many women’s accomplishments have been erased by the patriarchal writing of history, and so my goal is to restore Musidora to her much deserved place in feminist film history. She directed a dozen films, wrote several plays and novels, performed onstage, painted, sculpted. All of her films are lost but two, and the Cinémathèque française has restored them only recently.

They myth of Musidora was that following the great Irma Vep, financing dried up for her projects and that eventually she became destitute, spending her final days as a ticket taker in the Cinémathèque française. This is only half true. She did indeed work the ticket booth at the Cinémathèque, but she also worked as an archivist and researcher. She was involved until the day of her death. At the Cinémathèque you can find reams of her interviews with directors like Godard, Fellini, Antonioni. I also suggest reading Colette’s book, Un Bien Grand Amour: Lettres a Musidora 1908-1953. These are letters written from Colette to Musidora spanning their entire relationship which was simultaneously one of lover – muse, sister – sister, and mother – daughter. Through these personal letters you get a portrait of Musidora in absentia.

Most importantly, I want the audience to think about the struggles female artists have gone through to support their work, and how little of their work is restored or archived compared to male artists. I suggest people look at Women Film Pioneers Project: https://wfpp.cdrs.columbia.edu/ if they want to find out more about the vast roles women played in the development of early cinema.

AN: You have said elsewhere that you don’t necessarily resolve anything through your work, you ‘just keep getting deeper and unlocking more.’ What have you discovered working on Irma Vep, The Last Breath? Would you say there is a uniting theme to your work overall?

MH: Specifically though working on Irma Vep, The Last Breath, I would say I’ve learned more about the power dynamics between the visible and the invisible, and the ways we build our identities – how what we become is often different from what we want to become. And that’s okay. We’re all just trying to survive, and when we’re forced to live in a society that doesn’t accept diversity, we can lose track of our own identity as we wear masquerades for survival. Often transgression is simply a survival tactic.

I’ve always been motivated by Eros and Thanatos; the drive to transcend through excess and pleasure, and the solace of finding comfort in the abyss. The eternal themes of being human… life, death, sexuality, and how we construct identity in relation to resistance. I’m getting more and more interested in the depth of surface and how it relates to projection. In her most recent book, Giuliana Bruno talks about surface as a thin membrane that mediates between inside and outside, and that the mediation is a form of projection. I look at the screen as a surface of projection, not only as a surface for an image, but for the viewers’ psyche.